Shelton Laurel Massacre

On a frigid day in late January 1863, a tragedy of the Civil War left its legacy on the farm families of the valley known as Shelton Laurel. Unable to relate to the Confederate causes of slavery and secession, many of these families supported the Union. Yet, the War rationing of salt, critical for curing meat and survival, was controlled through the Confederate county seat of Marshall. Confederate troops had conscripted the Unionist men of Shelton Laurel, taken their horses and food stores, and sometimes assaulted the women. When the farmers were again denied salt during this cold January, a group of them rode into Marshall to demand their share. Tempers flared and buildings were burned or looted, including the home of Colonel Lawrence Allen, the 64th Confederate Regiment leader. His young children were there, sick with scarlet fever, and later died. Allen and his second in command, Lt. Col. James Keith, swore justice and rounded up any Shelton Laurel male they could capture. Several prisoners escaped and a frustrated Keith ordered the remaining 13 men and boys to kneel, where they were executed. Three of the boys were 13, 14, and 15 years of age. Their bodies were thrown into a shallow ditch, barely covered and left vulnerable to free-ranging hogs. The aunt of two of those killed, known as Granny Judy, along with her children, loaded the damaged remains onto an ox sled and carried them to a Shelton cemetery two miles up the valley, where they now lie in a mass grave on this lonely hilltop. Today, a granite

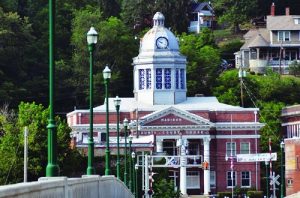

marker memorializes the site (although a Civil War Trails marker for the massacre is at a location 6 miles away). There is another Civil War trails marker at the Col Allen house in Marshall.